Are Major Labels Cooling On Viral Artists?

/After years of paying big for songs going viral on social media, labels' strategies may be shifting.

BY ELIAS LEIGHT

On Feb. 4, the rapper Superstar Pride posted a 19-second clip to TikTok of a somber song called “Painting Pictures.” He was basically unknown — with less than 1,000 on-demand streams in the U.S. in January, according to Luminate — but TikTok is famous for its ability to help newcomers attract eyeballs. The unadorned clip, just a rapper and a microphone marooned on a tennis court, quickly passed 1 million views on the app, and the week ending Feb. 9, on-demand streams of “Painting Pictures” leapt from negligible to over 130,000. Pride posted another popular video eight days later; the following week, on-demand streams ballooned to more than 4 million.

“There was this crazy conversion to streaming,” says one senior label executive. “[Pride] made the rounds; every label was talking to him.” But in the end, the rapper announced that he was staying with United Masters, which initially distributed the single.

Some artists prefer the independent route. “[Superstar Pride’s success] is just another example of an independent artist finding tremendous success without the need to give up his rights… to a record company,” United Masters’ Steve Stoute told Billboard in March. (The rapper’s path was also complicated by the fact that the Faith Evans sample underpinning “Painting Pictures” wasn’t cleared initially.) Still, some in the music industry saw this episode as a demonstration of the major labels’ more cautious approach to viral phenomena.

“Three or four years ago, if that bidding war had happened, it undoubtedly would have come to fruition,” the senior executive says — somebody would have made the rapper an offer that was too big to turn down. In 2023, however, “some labels are disillusioned with their viral pickups,” according to one music attorney who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “There have been a lot of losses. Buyers are going to be a little more deliberate.”

For several years, the mainstream music industry appeared fixated on signing acts with viral momentum. During interviews, executives described the process of combing through heaps of song and artist data from streaming and social media platforms, especially TikTok, identifying tracks with hockey stick graphs — numbers racing up and to the right — and scurrying to lock in a deal before their competitors. Privately, some expressed surprise that their job seemed similar to stock trading, while others criticized this signing strategy as basically buying up market share but foregoing the tough work of artist development.

Labels have been aware of social media’s power to drive wild surges of interest in songs for more than a decade — at least since Psy‘s “Gangnam Style” in 2012 and Baauer‘s “Harlem Shake” in 2013, if not before. In the years since, social media and streaming platforms have become far more potent, and labels invested heavily in honing their research, hiring data whizzes to develop tools that scrape these platforms top to bottom.

Every big label had access to the same pool of information from the social media partners, more or less, so speedy outreach to artists was essential. Even so, bidding wars were common. Especially in 2019, 2020 and 2021, “it felt like every single day another artist signed a deal that was a gazillion dollars,” says another music industry lawyer who requested anonymity to speak candidly. And in the mad rush to beat out the next label, the song or artist being signed sometimes seemed secondary to the data. “People are spending huge on sound effect records,” one senior executive grumbled in 2020.

The checks were big, but so were some of the hits — none more so than Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road,” an early beneficiary of a TikTok craze that went on to become the longest-running No. 1 in Billboard Hot 100 history. Still, even with a massive supply of data, forecasting the future remained notoriously difficult. Months of robust streaming for one single may say nothing about the fate of the artist’s follow-up.

Despite artists’ and labels’ best efforts, it’s now standard to hear that engineering a trend on TikTok is about as likely as buying the winning lottery ticket from the local corner store. And it’s a lottery that appears to have diminishing returns: Viral trends in 2022 did not translate to streaming platforms as effectively as they did in 2020. “All you can do is drop music consistently — and pray,” says another senior executive at a major.

Taking these factors into account, entertainment attorneys say the industry is starting to look more carefully at viral phenomena. “There’s a lot of viral stuff now that doesn’t get as much attention as it did a year or year-and-a-half ago,” says Leon Morabia, an associate at Mark Music and Media Law. “A lot of things that should’ve been signed to single deals, labels signed to record deals, and they ended up having to replicate the success and it was virtually impossible. And so they ended up with all these artists on their rosters that they had to service that weren’t actually more than a song. It was bad.”

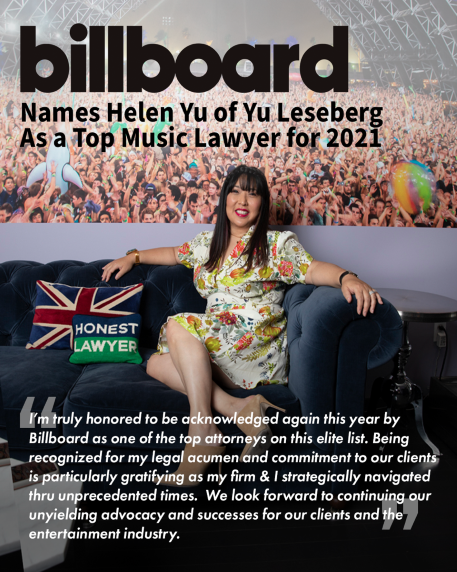

“The market has been correcting,” adds Helen Yu, founder of the music law firm Yu Leseberg. Labels “are backing off in terms of just chasing a number. At some point, it’s coming back to recognition of talent.”

That could be why music lawyers are noticing a new set of behaviors. “For a while there was a lot of signing going on sight unseen,” Morabia says. (The pandemic temporarily made this a necessity, but the need for speed meant the practice continued.) “I see a return to wanting to meet artists in person,” Morabia continues. “I’m hearing questions — ‘Can we meet the kid?’ ‘Can you send us the unreleased music?’ — much more than I did before.”

John Frankenheimer, chair of the music industry practice at Loeb & Loeb, is a veteran lawyer who jokes he’s “been doing this since dinosaurs ruled the earth.” “Opportunities like this always create a frenzy because people are curious to see how they can grasp the latest lightning rod,” he says. “Then everybody has to take a deep breath and start looking at this stuff a little more closely.”

BILLBOARD MAGAZINE: Are Major Labels Cooling On Viral Artists?